I feel bad for my friends.

I haven’t shut up about Ocean Vuong in recent weeks since reading his T. S. Eliot Prize winning collection, Night Sky with Exit Wounds. The 2017 collection is evocative and moving. Many of the lines within highlight the excitement and energy found within contemporary poetry:

& remember,

loneliness is still time spent

with the world.

Or, my personal favourite:

Sometimes I feel like an ampersand.

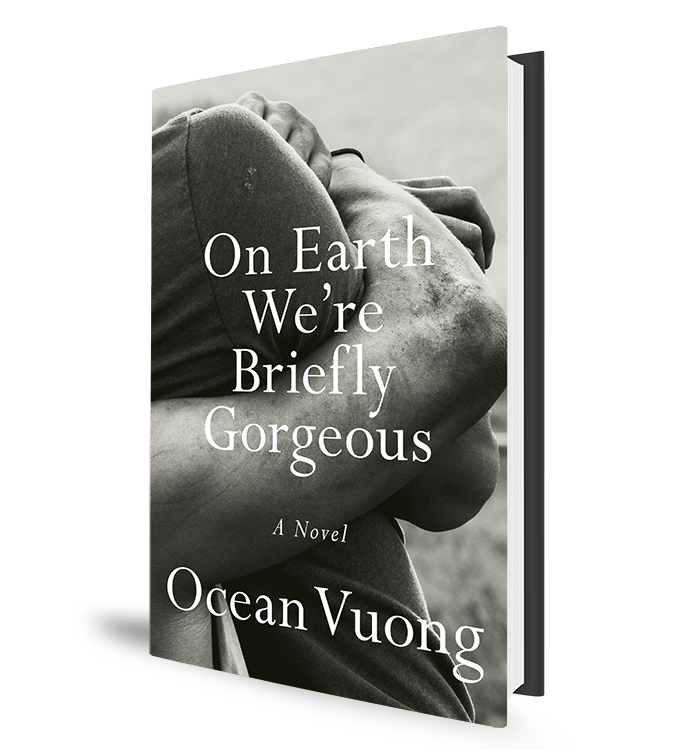

On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous is Vuong’s first novel. The title is taken from one of the poems found within Night Sky with Exit Wounds, a collection in which the poet considers his own family story. Family sits at the heart of this novel and so too do love, loss and life. The story within detailing the experience of a gay, Vietnamese-American teenager finding his way in the world is as moving as it is evocative.

The novel is written as a letter to the narrator’s mother, referred to for the majority of the book only as ‘you’. The narrator’s mother, we learn, is illiterate.

Little Dog, as he is called, is quiet, preferring others, whether it be the elderly Lan telling stories of Vietnam, or the boisterous Trevor, a fellow teenage worker on the tobacco farms, to do the talking. Though rarely speaking, Little Dog is a keen observer. Vuong’s writing pinpoints tender details in each of the characters and brings them to life.

[Mild spoilers ahead] The scenes of passion between Little Dog and Trevor are described with incredible tenderness. Vuong captures the youthful love of two teenagers, each different in their character and selves, yet intertwined, exploring one another while simultaneously growing and discovering the world.

The impression made by both boys on one other and on those around them – Little Dog’s mother, Trevor’s alcoholic father – is the extent of their impact. They are principally human, fundamentally unable to impact upon the world around them. Their gorgeousness, however brief, remains potent because the characters refuse to be defined by preceding events, whether that be the death of a companion, or the war in Vietnam. They resist definition and seek instead to redefine themselves.

My favourite scene takes place in a diner with Little Dog and his mother drinking coffee. Little Dog comes out as gay to his mother, who struggles to understand, assuming that he will now wear dresses. His explanation to his mother is, he feels, undercut by his mother’s tit-for-tat confession: that she had an abortion before Little Dog was born. This exchange is powerful, each statement working against the other, and yet the fraught and violent relationship of mother and son up until this point seems to reach a new level of maturity.

The poetic beauty of Vuong’s previous work remains front and centre within this novel. To finish with some lines of beauty from the poem of the same name:

& morning

finds our clothes

on your mother’s front porch, shed

like week-old lilies.