Online privacy. It’s a hot topic at the moment. The internet giants have been in the headlines almost daily, accused of abusing the data they have. With private companies tracking your every move online, the internet feels more unsafe than ever.

But, practically, what can I do to stay safe on the internet? Hopefully, we have some answers for you.

Background

The Internet. We all know and love/hate it. Chances are you’re reading this article online right now, instead of in our print edition.

For the internet to work, there is always going to be a trade-off. Service providers need to know some basic information (such as where you’re connecting from – we call this your IP address) so their websites work. As a result, wherever we go online, we’ll always leave a footprint on a digital beach somewhere.

For nearly two decades after the internet became mainstream, internet giants have built their empires on personal data, data which you provide. Without this data, there simply wouldn’t be a service. No Facebook friends or posts, no Instagram profiles, nothing.

The problem is, however, that for nearly 20 years there were no checks and balances around how companies could use this information. Essentially, it was a free-for-all. In 1998, the first data protection law was passed in the UK, but it still allowed companies to do virtually everything if they obtained consent (think that legalese wall of terms & conditions).

To put it simply, all free services are based on your personal data. Facebook costs billions to run, so instead of charging a fee, they use targeted advertising instead. However, these giants are now so big that they have access to more data than ever. This is literally the 21st-century version of “if it’s too good to be true [or free], it probably is”.

To try and set some ground rules on what this data can be used for, the EU brought in the General Data Protection Regulations – that GDPR thing you heard all about online. But, even with this regulation, the problem remains – nobody is explaining to us how our data is being used, and with increasingly complex systems powering these websites, chances are the internet giants themselves don’t know the full story either.

Our aim isn’t to scare you with this article, but I do think that the state of the internet is terrible and that more needs to be done to protect people who use it.

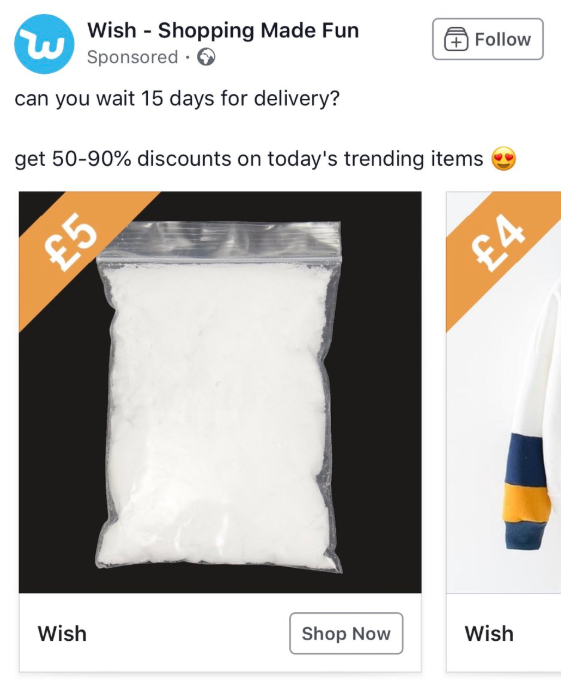

Advertising? The Wish Effect

Internet advertising has been around nearly as long as the internet. With the exception of nasty scams and malware things, and recent political scandals, for the most part, the advertising itself is harmless. For businesses, it’s the only realistic way to run a free website and generate income. But it is now possible for advertisers to target a specific person with a specific advert, with nothing more than their email address or phone number. If you started seeing lots of oddly-specific Wish adverts in your Facebook feed last year, that’s probably why.

Over the last ten years, there’s been a big shift in the industry, with giants trying to show us adverts they think we are interested in. If you can show a user a relevant advert, they’re more likely to click it.

But what makes an advert relevant? If it’s for a local business, we need to know where the user lives. If it’s for a new product, we need to know if the user is likely to have an interest.

Google and Facebook run the majority of advertising on the internet. Google run the popular AdSense programme, which lets website owners run Google adverts on their website to make money. Even though Facebook’s adverts only run on their sites (and sister sites like Instagram), they still have 2 billion people who use these sites monthly.

Before Google and Facebook started making big money from their adverts, there was a dilemma: how do we show people adverts they like, so we can increase our revenue? The answer was clear: we already have the data to do this, we just need to work out how to interpret it.

Although advertising was originally mostly harmless, the problem is that these internet giants simply don’t have any restrictions on what they can do with that data (especially as, in the eyes of the law, all these sites are one company). Google use virtually everything you do (from internet and YouTube searches to actual GPS location history – and even websites you visit in Chrome) to build a virtual model of you. Facebook does the same thing based on pages you like, Instagram profiles you follow, posts you make and interact with, etc.

That may be a pretty bold statement to make, but it’s a fact. They even state it in their Privacy Policy. But we know virtually nobody reads the T&Cs and privacy policies – they’re legal documents and they’re really complex.

As Internet giants get bigger, and more companies merge (like Google and YouTube), these companies have access to larger datasets than ever before. And recently, we’ve seen how disastrous the effects of this can be. Any advertiser with a load of cash can get access to these platforms. The Cambridge Analytica scandal proved this.

However, with the introduction of GDPR in Europe, the new privacy law, it’s now possible to opt-out of targeted advertising. But if you signed up to these sites before 2018, you have to turn it off manually.

Facebook has this hidden gem that explains how to opt-out of targeted ads

Google has a similar guide, too

Companies Misusing Your Data

People on the internet have been complaining for years that Facebook was abusing personal information. It was only when the Cambridge Analytica scandal happened that the concerns about privacy became a major political issue.

We give Facebook, Google, etc. a lot of data. Every search query, every message or email, and every post and comment. Machine Learning (aka AI) has largely allowed internet giants to profile you with much more accuracy, as they can compare datasets of billions of people. But there’s every possibility that this data could be shared with a third party.

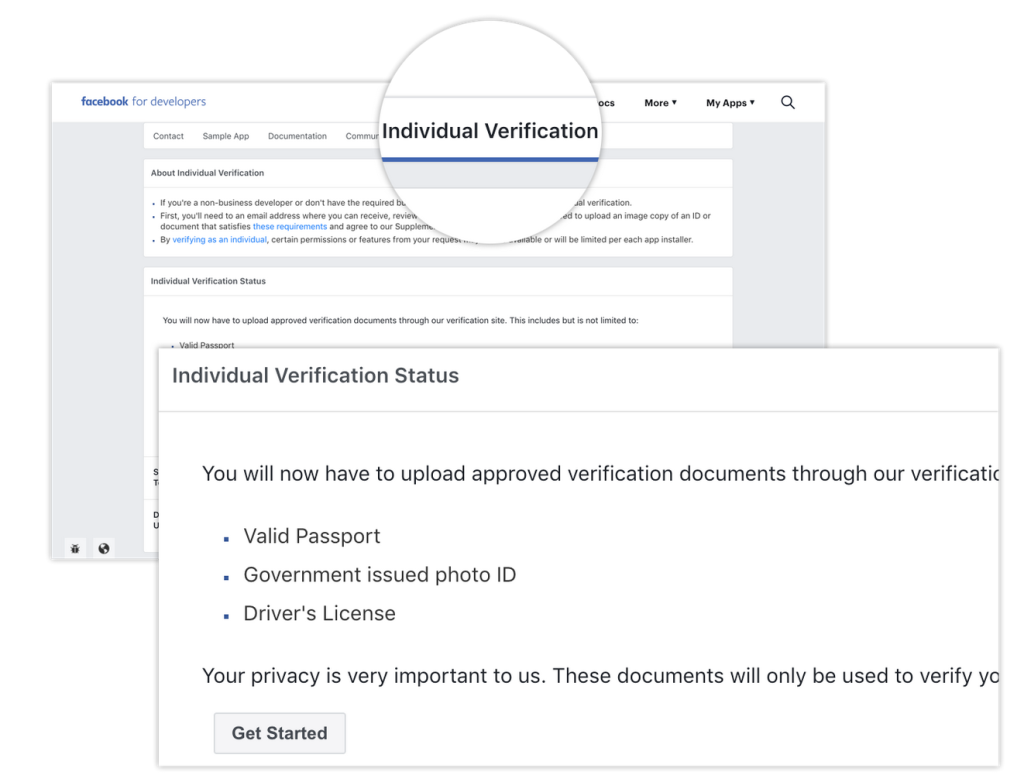

Virtually every social media website has a set of developer tools, known as APIs, that allow third parties to build apps on top of their websites. However, even to this day, these APIs let developers find information on people who have nothing to do with these apps.

If you ever used FaceApp, or another viral Facebook app, just by logging in you give a third-party company access to your name, your entire friend list, email, and photo. If one of your Facebook friends used one of these apps, it’s very likely that those developers had access to some of your basic personal information. It is alleged that Cambridge Analytica used this data to build a database of potential voters, political affiliations, and their personal or political beliefs.

Facebook apps don’t tell you what your data is being used for. Or who’s getting access to it. The company seemingly makes no effort to verify a developer’s identity, or validate that companies that sign up for that service are real.

Give a man a bank and he can rob the world. Give a bad actor a viral app, and they can rob the world of their personal information. Data collected through apps (like email addresses) suddenly becomes useful in marketing campaigns, and political campaigns can now individually target millions of people at scale.

The solution of “make a developer sign a contract that won’t let them misuse their data” didn’t work, because, unsurprisingly, some developers were abusing data they had access to. Like with stolen goods, it can be impossible to trace stolen data – or even know what was taken.

Although Facebook’s data sharing really does serve legitimate purposes (think lots of business tools and things like “Log In with Facebook”), we discovered that it’s possible to gain access to information on people simply by signing up for a developer account. Before gaining access to live data, they would require you to verify your identity in the form of a scan of your driving licence or passport. However, it may be possible to fraudulently provide a scanned identity document. Facebook state that they delete this information after verification. I can’t help but find that ironic.

The only real solution to this issue at the moment is to not use apps you don’t trust, and to lock down your privacy settings to avoid people you know accidentally giving away your info. It’s not worth looking at a 20 years older photo and giving your information to a potentially untrackable anonymous company.

I know a lot of my friends feel that Facebook’s apps ‘hear’ things they shouldn’t. For instance, they might talk about going on holiday to a specific place, and then adverts for that place suddenly appear. There’s no evidence at the moment to support whether or not this is true, but that would probably be a breach of data protection law.

What Can I Do To Protect Myself Online?

To start with, there are lots of ways to opt-out of ‘data collection’. This makes it harder for advertisers (or bad actors similar to Cambridge Analytica) to target you personally.

Google now lets you turn off “Web & App Activity”, which they claim stops this data being processed. Click here to find out how to do this.

The Internet itself is fighting back. Private browsing disables a lot of the technology companies will use to track you across the internet.

The Firefox web browser has a built-in tool that stops trackers from working. Chrome, however, is developed by Google and is actually worse for your privacy.

I think it goes without saying that these companies should do more to stop people misusing the data they have. Facebook provide their staff with tools to protect their data, so clearly the giants realise this is a problem, but have no interest in helping the average user.

Here are some other helpful privacy tips:

- VPNs don’t make things more secure. If you’re not using private browsing, you’re still logged in after you turn your VPN on, so companies can still track you. In fact, advertisers can see you’re using a VPN and there’s more information to target you with. VPNs are a great tool if you’re using free/public Wi-Fi, but they don’t really help us here.

- Be wary of Cookie Preferences and dodgy prompts! Some companies intentionally make it really hard to opt-out of marketing. For instance, they might swap around the buttons, or have checkboxes ticked by default. This is technically illegal under GDPR, but companies based outside of Europe seem to be doing this.

- Be careful when using your phone number! Unlike email addresses, where you can have many, you probably only have one number. Advertisers can use your phone number to target you, too. When signing up for services, use an email address where possible.

If a company wants you to verify your phone number, they should ask you before they use it for marketing. This might be written in the small print. - Use different email addresses where you can. To stop the Wish Effect, try and use different email addresses for social media and other websites online. If you’re using your Royal Holloway email, you already have a few different emails, such as:

- Use the kill switch. If you don’t want companies to use this data any more, you have a legal right to ask them to delete all your personal information. Obviously, this would close any accounts you hold with them, but a digital detox might not be the worst idea.