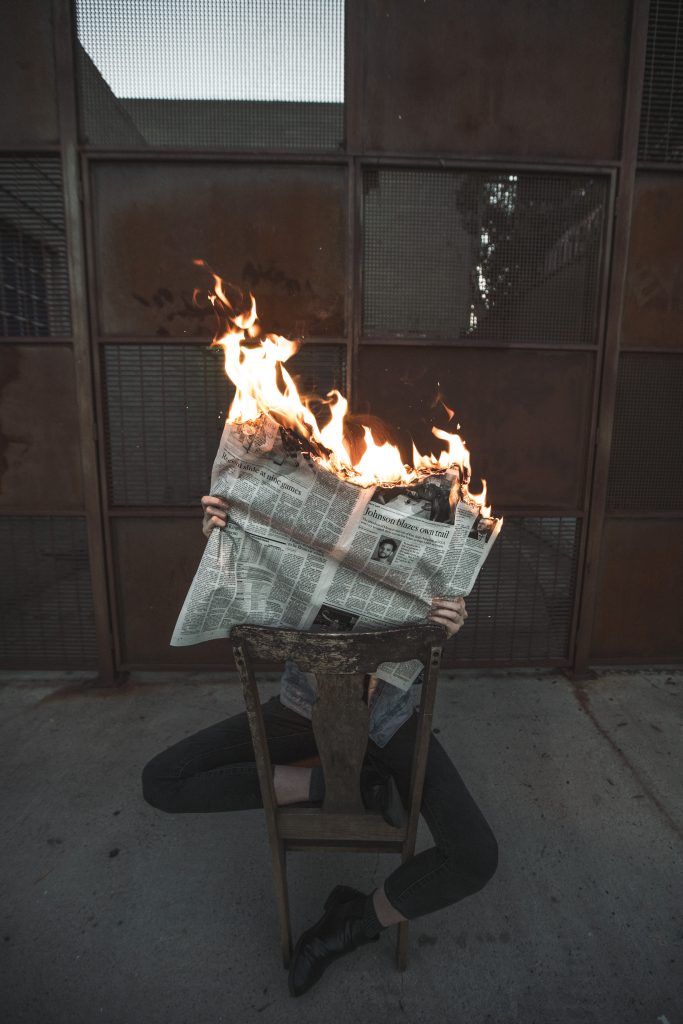

How technology is helping to disrupt the truth

‘Fake News’ is a phrase most frequently associated with the likes of Donald Trump, pointing the finger at journalists for their sensationalist, subjective reporting and blaming them for the hate he received by many. Journalists have a lot of responsibility in that regard – we are a society built on the opinions of the masses and journalists have a large stake in swaying that opinion. Many also associate this issue with a rising ‘cancel culture’- one bad word and the twitter cavalry storm in.

In the twenty-first century, we have got endless information at our fingertips. Thanks to the internet, we can momentarily discover breaking news or the height of a favourite celebrity; any kind of information that will satisfy a curiosity and allow you to figure out how to build that Ikea coffee table. The internet is, in many ways, this incredible invention most Brits can’t imagine life without. However, as with all things, it has its downsides. We can get brand new information quicker than ever, which in turn means journalists are biting at the bit to get out the next news story; this often means that much of the information has not been backed up and that it could, in fact, be just a rumour. And it’s not just the information we are given, it’s the information that news broadcasters, or platforms and companies, can choose not to give us. After all, as Sir Francis Bacon once said ‘ipsa scientia potestas est’ – Knowledge itself is power.

Our dependence on technology is always going to be a contentious issue; the general feeling towards this era of technological reliability in journalism is put succinctly in an article by the editor in chief at The Guardian, Katherine Viner. She writes how “in the digital age, it is easier than ever to publish false information, which is quickly shared and taken to be true”. Not only does this mean that some of the information is censored, but that rumours can spread at alarming rates. She is referring to the use of social media. It is easy for anyone to read a post and share it to let everyone know about this information, or for anyone to make up stories under the pretence of ‘fact’ and share it without any evidence. And with our busy lives we tend not to have the time to check the facts, we just assume and trust that the information we are provided with is true.

Social media is not only a place to spread information but also a place where companies can censor what information we are presented with online. Unless we are actively searching for a particular topic, it won’t be shown on our social media feeds. Viner writes about how “algorithms such as the one that powers Facebook’s news feed are designed to give us more of what they think we want – which means that the version of the world we encounter every day in our own personal stream has been invisibly curated to reinforce our pre-existing beliefs.” This is particularly an issue in politics. If we are given information about a campaign or about someone running for prime minister then that information may sway our decisions about what or who we vote for, if after the decisions have been made and we find out that that information was in fact false then we may look back on our vote and regret it – then we have the issue of whether there needs to be a revote (like with the Brexit’s ‘vote leave’ allegations).

Facebook has pledged to begin to do something about this ‘filter bubble’ (as Eli Pariser, the co-founder of Upworthy, coins it). Although some claim this is merely a clever marketing stunt, and further evidence of Facebook’s denial of responsibility. The backlash to their rebranding as ‘Meta’ demonstrates how skeptical people are to trust Facebook.

Many people today rely on social media for updates on current affairs and to help construct their opinions, but how can we objectively do that if there’s a good chance the information is biased, rumour or simply untrue? We are unlikely to double-check these ‘facts’ in our busy lives; we regard them as truth without any further investigation. After all, the news is meant to be reliable and ethically reported.

Many writers in the past have talked about issues with misinformation, the most famous of all being George Orwell in Nineteen Eighty-Four. The phrase Orwell uses is “Freedom is the freedom to say that two plus two equals four” in other words, freedom only exists if all the information we are given is concretely true. He comments on how easy it is for those in power or those we put our trust in to say that “two plus two equals five”. Sales of Nineteen Eighty-Four shot up when Trump ran for president, with people making links between modern society and the dystopian world Orwell presents.

It’s not that all the information we are presented with is false, nor that falsifying information is the aim of most journalists, only that perhaps we need to be wary of what allegations given by the media are true, and how narrow our information ‘bubbles’ might be. This starts with checking sources and reading around – to ask ourselves if the information we are provided with is fact or fiction.