Warning – this article contains spoilers.

With it being Halloween, a lot of us will be spending the season in various ways. Whether it is going out to the SU dressed up in costume, or snuggling up under a blanket and watching a scary movie. Nowadays, we are spoiled for choice with what films we can watch, because horror films have many sub-genres. For example, a sub-genre in horror which always fascinated me was the ‘slasher film’. This was primarily because all the slasher films of the 70s, 80s, and 90s ended in the same manner. There was always a ‘Final Girl’ who overcame the killer and survived. Admittedly there were different variations of the Final Girl trope. One could easily point out a contrast between Jamie Lee Curtis’ virginal Laurie Strode in Halloween (1978), to Olivia Hussey’s non-virginal Jess in Black Christmas (1974).

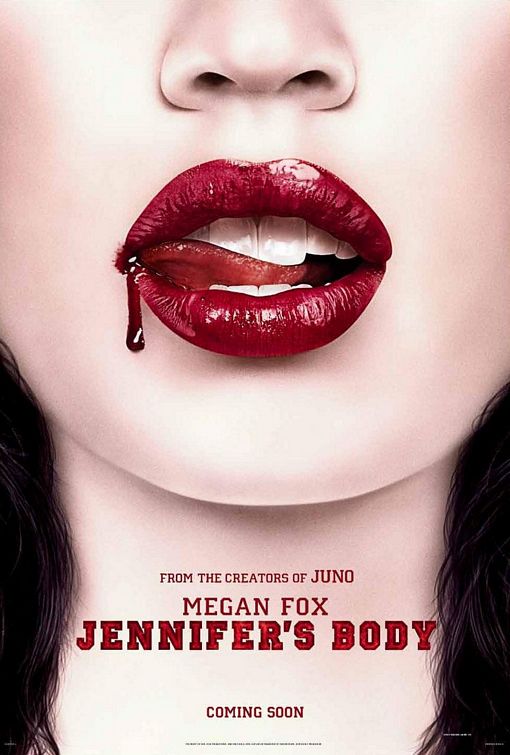

Despite all the different variations of the final girl, the trope appeared to be done to death. That was until 2009 when screenwriter, Diablo Cody, subverted the trope even more so in Jennifer’s Body. The horror film centres around popular high school cheerleader Jennifer Check (played by Megan Fox), who gets possessed by a demon and proceeds to kill her male classmates. If you ignore the fact that this plot sounds like a grotesque raunchy sex comedy, when watching it you can appreciate that it is actually a revenge flick. In an interview with Jennifer Kwan, Cody said that she and the director, Karyn Kusama, “wanted to subvert the classic horror model of women being terrorized.” This ideology therefore aims to take away the male gaze, which can detract from the flaws of the final girl trope.

The film was unique in that it was a female-led horror story for teenage girls, but due to severe mismarketing, symptomatic of a culture where the male gaze is prioritised, it bombed at the box office. Fox studios wanted to capitalise on Megan Fox’s sex appeal by marketing the film for college aged men and even worse, suggesting that they advertise on film amateur porn sites. This feels blatantly crass given that the film was written for teenage girls. It was also horrifically ironic that a film which poked fun at sexism was mismarketed due to sexism itself.

Diabolo Cody talks about this mismarketing in a video interview between her and Megan Fox for ET Live, which marked the 10 year anniversary of the film’s release. Cody noted that she remembered a specific exchange, where she put forward an articulate email over how the film should be marketed. This marketing person only responded to her with three words: “Megan Fox Hot”. Evidently Fox’s good looks had become what the studio viewed as “the core value” of the film. Overall, this was a product of a male dominated industry, trying to have a say over something which was never meant for their ideal demographic.

In going back to the ‘Final Girl’ trope and how Jennifer’s Body subverted it, we have to look back at previous iconic slasher films. In a lot of these films, once the final girl has managed to escape the clutches of the killer, there is a very eerie unsettling feeling that what they have gone through is not over yet. This harks back to the ending of Halloween (1978) wherein Laurie Strode is sobbing in fear, as her rescuer notices that Michael Myers has escaped and could be anywhere. This sort of ending makes it clear that the final girl is doomed to be scarred forever, hopelessly trying to evade something which will never go away. Jennifer’s Body does not end in typical final girl fashion though. It begins with a final girl and explores her journey in the style of a vengeance flick. Upon being sacrificed by a group of men, Jennifer becomes the final girl that was never meant to survive. The trauma her body has suffered causes her to become possessed by a demon. She uses her powers to get revenge on those who represent a section of society that have wronged her. Think high school males. In 2018, Constance Grady wrote in Vox that the film is a “revenge fantasy” where “Jennifer uses her abused body against her attackers.” Evidently, Grady emphasises that the film’s resurgence in popularity can be credited to the ‘Me Too’ movement. Jennifer’s Body takes the ‘horror female’ trope and rearranges her into more than a victimised final girl, and it is this that resonates so deeply with contemporary culture.