In the early hours of the 23rd of December 2021, Hong Kong University’s Pillar of Shame statue was removed from the centre of campus. It has stood there at the University of Hong Kong since 1997 and represented the numerous lives lost in the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, one of the most delicate topics in Chinese politics. Recently replaced with a new seating area, no remnants of the statue remain onsite. The image of the orange twisted bodies imprinted only in memory.

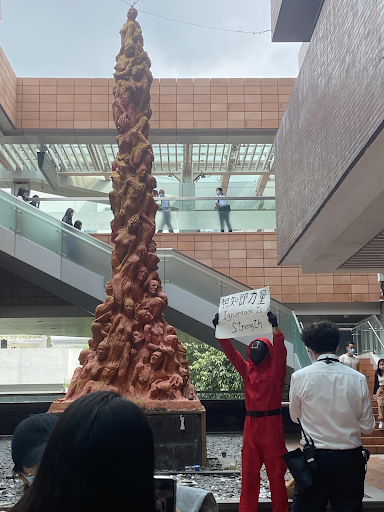

The Tiananmen Square Massacre has largely been erased from history in Mainland China and Hong Kong is now following suit. The Pillar of Shame stood as a symbol of the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong, highlighting the difference of freedoms between Hong Kong and the Mainland, a gap that is being gradually closed. The eight-meter-high statue was created by Danish sculptor Jes Galschiot and stood outside the main canteen where several students, staff, and other members of the public regularly ate meals and passed by. The statue was a part of daily life. Its removal demonstrates further erosion of freedom of expression in Hong Kong, and an increasing presence from Beijing.

Recently, in the United States and in Europe, the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests demonstrated that society is long overdue for an evaluation of what should be championed and displayed in public spaces.

The question of monuments was greatly addressed with several taking to the streets to vandalise and topple statues of slave owners and other symbols of hatred, inequality, and oppression. Statues honoring a past that is no longer coherent with the values with which we live our lives, or the future we wish to build must be dealt with. With the toppling of statues more associated with progression, it is important to acknowledge the damage caused by the removal of those that should remain.

This is the opinion of several students and visitors at Hong Kong University, one of which protested in front of the statue dressed in a red jumpsuit and mask from the popular Korean series ‘Squid Game’. Their choice of costume appealed to the several people who had recently watched the violent, dystopian series on Netflix and the sea of red that took to the Lan Kwai Fong district on Halloween, donning the same red jumpsuits. Holding a sign reading ‘Ignorance is strength’ from George Orwell’s 1984, the solo protester drew parallels between the two well-known dystopian narratives and the Chinese Government.

Statues and Monuments are the physical bolting down of ideals and ideas made to stand tall.

Statues and monuments are the physical bolting down of ideals and ideas made to stand tall. They are built to remain. When these physical displays of the past are removed it is symbolic. In the case of the statue of Edward Colston in Bristol, the toppling of his statue was a symbol of progression. It represented the removal of a piece of history that was moralised and weaponised against the oppressed. Such is the historical weaponisation of the public space. Yet, in the case of the Pillar of Shame, it is its absence that is detrimental. It carries a deeper message of the suppression of civil society and an attempt to restrict basic freedoms, as a result of the new national security law brought into place in 2020. It is its removal that signifies oppression.

From the moment the removal of the statue was announced in October 2021, a melancholy and anxious sentiment descended upon the university. Several students were emotional about the topic and flocked to the main canteen to eat beside it day after day and ensure its place in their memory and in photographs. Others took to social media to share news reports, images and their heartfelt reactions. Months later, after students had finished their semester and were occupied with their time off, the statue was removed overnight, raising feelings of anger and betrayal at the sly act. Some went to see it as soon as they heard the news, finding only a cordoned off zone. Others waited until they returned for their second semester where they soon found the new seating area in its place. The full impact of the removal has not yet been processed as several students remain at home, not having returned to campus due to the unfolding Covid-19 crisis currently affecting Hong Kong. Nevertheless, for those who have returned to campus, it is not hard to notice the torment, when people walk past or eat lunch, where the twisted bodies and screaming figures stood, nothing remains.

For several years students gathered annually in a ceremony to wash the statue on the 4th of June whilst other vigils took place across Hong Kong, forming a part of its collective memory. Victoria Park was the location of an evening candlelight vigil that took place every year for 30 years since the tragedy. The existing police ban of the events saw the arrests of several people who defied the ban in 2020 and 2021. In addition, with Covid-19 only just hitting its peak in Hong Kong, it is also uncertain what related restrictions will be in place on this year’s anniversary of the Tiananmen Square Massacre. It is likely that the several thousands of people who would gather in Victoria Park prior to the ban will light a candle in the privacy of their own homes, some of which are no longer in Hong Kong as they flee the political situation of which this removal is a symbol.

The area where the statue stood is now a seating area with a few round-shaped seats and potted plants. For newcomers, the seating area will be how it has always been, year after year leaving fewer people with the memory of the statue and its meaning. For the moment very few people use the seating area, as if out of respect for the statue and the cause, but it remains to be seen how this will change over time. This is also a tragedy from an educational standpoint. Several people from all over the world visit Hong Kong University, including several exchange students, who have been lucky enough to attend this year despite the ongoing pandemic situation. When speaking to several exchange students it was evident that the hard to miss statue had raised several questions and inspired them to educate themselves on the history of the Tiananmen Square Massacre as well as other historical details about China. It is a tragedy that it is no longer there to serve this purpose.

What we cast in iron, carve in stone and display on our street corners is symbolic, and if no plinth remains and no information is shared then we may not remember. Thus, the message in what remains and what does not must continue to be documented and recognised in an effort to progress and not erase history. In the case of Hong Kong, it is monumental harm that remains.

Photo by Sofia Bajerova