How effective is the Strike action in creating the change it seeks? An Interview with James Smith

The end of March will see the disappearance of professors from classrooms once again. Not because of the COVID-19 pandemic, but because of industrial strike action from the UCU (University and College Union). As a third-year student my university experience has been impacted by both the strikes and COVID resulting in an unexpected minimal amount of time spent on campus. In my first year there were extensive strikes which some students joined in on. Then COVID struck in March, disrupting the entirety of that year. Now, we are partly back to campus with both covid and strikes interrupting simultaneously. Professor James Smith, the UCU representative within the English department here at Royal Holloway, recognises that we ‘are a uniquely hard done by generation’ and also that he doesn’t ‘know any colleagues who didn’t have to take a deep breath before committing to depriving you of yet more education.’ They don’t do this lightly.

There are ‘four fights’ that the UCU seeks to address and dispute. This time James says that ‘the main reason [for striking] is the devaluation of our pensions by the sector’s private pension fund – the Universities Superannuation Scheme – which will make staff at least 35% worse off in their retirement.’ He gives three reasons for why this is problematic:

‘First, as is true of every area of work, pensions aren’t a gift to keep us happy in retirement, but earnings we have gone without during our careers. Any attempt to meddle with them should be taken very seriously.

Second, pensions are a particularly sensitive point for academics, because university teaching is unusual in being a professional job that can take a decade or more of training and insecure work to get into. I myself did not have a permanent job until the age of 30. Insecurity in our early careers should not now be matched by insecurity in old age.

And third, the way the pension devaluation was carried out was, in the eyes of many experts, insultingly dodgy.’

The reasons for going on strike are commendable and the professors often lose their pay for the days that they go on strike, but how effective is striking at creating change within university institutions?

I remember the extensive strikes in my first year at University in 2020 and was shocked at how little teaching I was getting considering the cost I was paying to be there. James calls this period ‘the most ambitious strike action’ in his lifetime, a strike that ‘followed an initial revaluation of the pension fund in 2017, where university chiefs were accused of having exaggerated the extent of the pension fund’s deficit.’ The result? ‘They agreed to look at the sums again, only to return to staff with yet further pessimistic calculations. It turned out these were ludicrously made on the basis of the value of the pension fund’s assets in March 2020… during the temporary economic meltdown of the initial COVID-19 shutdown!’

He says the ‘big escalation of industrial action in 2018 seems a little like a dream now’ with big ideas, fewer global problems to contend with and also ‘Picket lines around College [that] were busy with staff and students protesting together, and university buildings [that] were militantly occupied by students around the country’. A support that he explains as being due to ‘the surprising success of Jeremy Corbyn in the General Election a year before, and [because] the wind was generally in the sails of young people and the left.’ These may be ‘sadder, harder times’ but he thinks the unions’ continuation to fight and group support ‘serve as a reminder that nothing ever got better without organised collective struggle, and that universities can be more than money-making machines and are worth fighting over.’

“Universities can be more than money-making machines and are worth fighting over”

So perhaps then the industrial action is less about immediate change, but rather about inspiring hope and spreading wider ideas about the functions of, and injustice within, university institutions.

For James Smith the strikes are reminiscent of wider political problems. He recalls that ‘last autumn, Martin Wolf, chief economics commentator in the Financial Times, wrote that ‘Universities are also more or less immortal institutions. If they cannot afford the benefits promised in their scheme, nobody can’. Slightly surprisingly, that is to say, even capitalism’s in-house newspaper is siding with the strikers.’

Universities are businesses but not in the traditional sense. As students we are the customers of the University but for the majority of us the government pays our fees. With the money out of our hands it’s not like we can ask for a refund when we are not getting the education we signed up for. When putting this to James he said ‘despite governments hoping that fees would turn students into mere consumers, most students don’t see themselves that way and think it’s bad too’. Governments may be in part to blame with some level of control over Universities but we are still paying into a business. We go to university for the product, the teaching, but also for a learning community too. He hopes that the university can be seen as ‘a space for political struggle and contention itself’ and that ‘we can work on building more space for thinking and acting together’, staff and students.

So, what can Students do to help?

“Please complain about the situation to the Principal and Vice principals”

‘Our absence from work is causing all kinds of desirable chaos in the workings of our institutions’ administrative processes. But the only real way we can put pressure on our employers is by withdrawing from our most front-of-house work: teaching you. If you are irritated by this, then you should be! Please complain about the situation to the Principal and Vice Principals. Beyond this, the return from lockdown has been marked by students being far less confident about attending class or discussing their studies with their teachers one-to-one. Let’s change that. When the strike’s not going on, we want to be talking to you about the subjects and research we are so passionate about. That’s what we want to be doing. That’s the important part.’

‘If there’s one lesson I hope students can take from these strikes it’s that you should always stand up for yourself when your employer (here I refer to the universities leadership in the UK in general) insults you, and I hope you will take that lesson into your own career.’

So, striking around universities nationwide continues as the justice teaching staff fight for continues to be denied to them. How effective is the strike action? As with many protests, strikes have become more of a symbol. They are a direct response to the ‘insults’ staff face within institutions like Universities. Without a direct consumer – authority financial impact, the strikes serve as a consistent fight that little-by-little may produce the changes that are being sought.

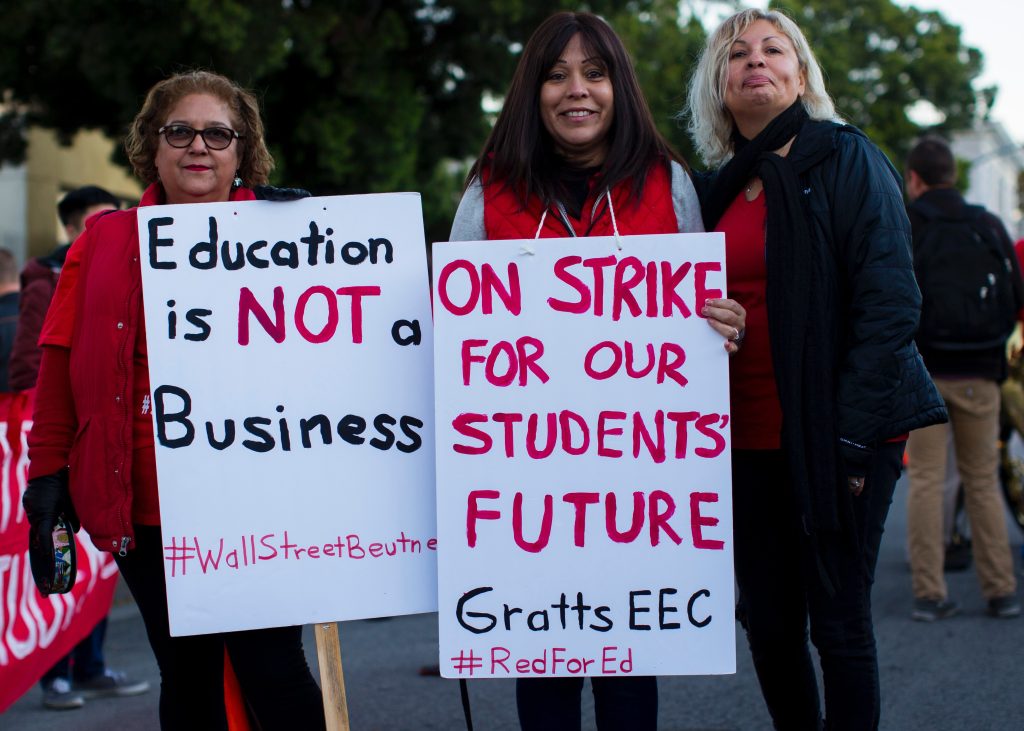

(Photo by LaTerrian McIntosh on Unsplash of education protests in LA.)